* * *

The clock chimed once, twice, two low notes that seemed to freeze like ice drops in the darkness. I opened my eyes, blinking against the cold, and saw the hard white shape at the foot of my bed.

“You’re awake,” she said.

I sat up, pulling the blankets tight around my bare shoulders. Rohese was already dressed, her white hair tied back in a queue with a heavy black ribbon. Her hands were covered with a pair of traveling gloves so thin, I could see the shape of her bones underneath.

“Where are you going?”

“I didn’t want to wake you,” she said, lowering herself to the corner of the mattress. Her voice was as cold as the clock’s chime. I tried to take her hand, but she lifted it lightly out of reach. “But since I did, I suppose I should say goodbye.”

“Why? Where are you going?”

“Does it matter?” Her lips twisted for a moment, but her voice remained hard. “You won’t be able to follow me, Loïc. I don’t want you to see…”

I let her words hang in the air for a moment. A naked plane tree branch raked against my window; somewhere in the tenements beyond, a child began to wail. “What don’t you want me to see?”

She didn’t answer at once. Hesitantly, I leaned across the bed and folded her in my arms. She turned her head, not so much kissing my shoulder as grazing it with her cold, dry lips. “I don’t want you to see my weakness,” she whispered.

“You aren’t weak.”

She raised her lips to my neck, and I felt the sharp teeth beneath them. Inexplicably, I remembered a November morning of a year before, the prickle of dry grass against my back, the shadow of a moth moving across Rohese’s cheek. My grip on her waist tightened. “How long will you be away?”

“I don’t know.”

On the street corner below, a lamp flame flickered and died. Rohese’s eyes became two purple shadows, dull and tearless.

“Will you come back?” I asked.

Her lips moved soundlessly against my skin. Yes.

Was

“All right, Franseza,” I said. “Which one of them did you want me to meet?”

They sat in a tight knot around the oak tree at the northern edge of Belmont Park, bathed on one side in the golden September sunlight and shadowed on the other by the lime-white cliffs and ruins of Rosewinter fortress. I knew most of them by sight; the children of wealthy southern families, sent north for the season to escape the sickly Plantation miasma. Despite the approaching autumn, they dressed in summery silks and dyed cottons. One of them, a young man with loose red curls and a firm red smile, was staring at my sister in unconcealed appraisal.

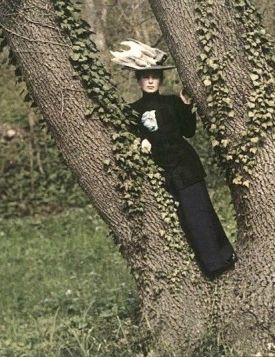

Franseza returned the smile, but her eyes rested on someone farther back. I squinted into the shadows beneath the fortress’s cliff and saw a woman sitting on a shelf of rock, her elbows resting on her bended knees. Like the others, she’d tied her hair in a waist-long queue, but it was as white as the stones of the ruins. She wore a linen shirt and gray waistcoat with a carelessness that suggested she’d wear the same thing in the dead of December or the middle of July.

“That’s her,” Franseza said, catching the drift of my gaze. “Rosewinter.”

Stupidly, I looked up at the constellation of vine-choked walls and turrets at the top of the cliff. Franseza chuckled and flipped a lock of hair over her shoulder. “No, that’s not her real name—it’s what Corentin calls her. But it fits, don’t you think?”

I turned again to the woman in the shadows. She had moved to rest her chin on her folded hands, and her lips were pressed tight in an expression of interest. Nothing about her suggested age or ruin—now that I looked closely, even her hair seemed warmer, closer to the color of water-light than the color of limestone. “I don’t know,” I said. “You’ll have to introduce us.”

The southerners looked up as we approached; Corentin, the red-haired man, languidly raised his hand in greeting. In her rough wool gown and fraying braids, Franseza looked like a serving maid at a Plantation ball. I ached for her, all the more because she did not seem to notice the contrast, while her acquaintances clearly did.

All except for one—the woman called Rosewinter. She greeted us with a tilt of her head, her eyes narrowed so that I could not make out their color.

“Who’s this?” she asked, glancing from me to Franseza. Her voice was firm to the point of harshness, and I realized, to my surprise, that I had expected it to be melodic.

“My name is Loïc,” I said, offering my hand. She took it in both of hers; her palms were dry and cold as winter.

“Rohese,” she replied. “Though Franseza has undoubtedly told you about my pet name.”

“She has. But I wonder why—”

“Loïc’s studying to become a doctor,” Franseza interrupted. I frowned at her—she was seventeen, old enough to know better—but she continued unperturbed. “He didn’t even want to meet you, Rosewinter, he was so wrapped up in his books. But I told him fresh air would do a world of good—”

“And now I’m here,” I finished. So Rohese’s name was apparently a dangerous topic; I would have to keep that in mind. I glanced at Franseza, but she shrugged shyly and stepped back into the waiting circle of Corentin’s arms.

“All right, sweetheart,” Rohese said, her voice a strange mixture of dry and tender. “You’ve done your job. Keep these weed-growing dandies amused while your brother and I talk.”

To my amazement, Franseza and the knot of southerners nodded and began to follow the trail down to Belmont Park’s lily fountain. Rohese chuckled under her breath.

“Well, Messire Loïc, it’s good to finally meet you. Franseza shares your opinions with us quite frequently—in fact, they’re the only opinions in Belmont I enjoy listening to.”

“And which opinions are those?” I asked, slightly flustered. Now that we were alone, Rohese’s voice took on a new tone—she sounded like a chess master laughing at an amateur’s mistakes.

“Let me answer your question with a question. Why do you want to be a doctor?”

She leaned back on the limestone ledge, leaving a place for me to sit beside her. I knelt down slowly, keeping my eyes fixed on her colorless ones. “I don’t know,” I said. “It’s just something I’ve always wanted. I…I hate suffering. Destruction. Whatever goes against the natural order of things.”

“Ah.” Rohese leaned forward. “But what if suffering is the natural order of things?”

Her face was pale, paler than I’d expected, though it seemed almost golden against the gray-white of her hair. Her expression was one I’d never seen before—like fear and pain and eagerness all at once. I wondered just what it was she wanted from me.

“Pain is unnatural,” I said, sitting back on my heels. “I don’t know how to argue it so that I can convince you southern University gentles, but it’s true. I feel it with every cell in my body.”

“I’m sure you do,” Rohese said. She made a gesture with her left hand, like pushing a pair of spectacles up the bridge of her nose. There was a strange gentleness to the motion. As she lowered her hand, I reached out and caught it in mine.

For a moment, surprise cleared her face of all other emotions. Then she smiled and raised our joined hands to my cheek.

“I feel things too,” she said. “And right now, I feel like I should show you something, but I’m afraid of what you’ll think.”

“What is it?”

She shook her head and extricated her fingers from mine. “You’re not ready for it, and neither am I. But we will be, someday soon. When I come to you again, you must not refuse to see me.”

“Why would I refuse you?”

The smile vanished. “Because,” she said, “I mean to show you that you are wrong.”

“About what?”

“About everything.”

We didn’t meet again until November. In the mean time, I applied and was accepted to an Academy of Medicine some fifteen miles south of Belmont. I spent much of my time there, above a florist’s shop in the suite of rooms that I shared with three other students. During the few Sunday hours I was at home with Franseza, I found myself reading fervently, as though I was looking for something in the pages. Whatever it was, I can’t say that I found it.

I was thus engaged on an unseasonably warm day towards the end of the month when I heard a knock at the parlor door. Franseza was out for the day—most likely with Corentin, who had decided to spend the winter in Belmont rather than on his family’s plantation—and while I would have preferred to keep reading, I knew it would be useless to pretend I wasn’t home. With an affected sigh, I lifted myself from my chair by the fireplace and opened the door.

Rohese stood on the other side. It took a moment for me to recognize her. Beneath a black coat and waistcoat, she wore a silk shirt of vibrant vermillion, flowing with ruffles at the neck and cuffs. Her hair was braided, not like Franseza’s fishwife plaits, but in a complicated net held together with golden chains. On my sister, the ensemble would have been stunning; on Rohese, it looked grotesque.

“Ready to be proven wrong?” she asked.

There was something wrong with her voice; it was dry and fast and mostly breath. She didn’t wait for me to answer, but grabbed me by the wrist and pulled me out onto the damp sidewalk boards.

“Wait!” I said. “Just let me get my coat.”

“You don’t need your coat. Come on!”

She led me through the muddy streets, dodging coaches and cursing pedestrians, over the Cape bridge and into the part of the city where townhouses replaced tenements and the flower-girls on the street corners dressed in prim hats and aprons. We were headed to the park, I realized, but not by the normal route. This path would lead us to Rosewinter.

At last we reached the courthouse, with the steep flight of steps in back that lead up the cliff to the ruins. Rohese paused a moment to shrug out of her coat and drape it over the newel post. “That’s so they know we’re here,” she said. “No one will disturb us.” I nodded and followed her up the stairs.

All that remained of Rosewinter fortress was a ring of limestone walls and a handful of narrow, crumbling towers. The courtyard paving stones had long ago been overgrown with weeds and a few patches of grass. Where the mortar had disintegrated between the stones of the walls, black vines took root, spreading across the white face like a bloodstain.

“Rosewinter,” I said. Rohese glanced at me, her expression unreadable. “Why do they call you that?”

“This is where Corentin met me.” She knelt down in a patch of dry grass in the shadow of the northern wall. Against the mass of vines behind her, her hair looked like the moon in a pitch-black sky. “He and your sister, I mean. They come up here to be alone sometimes.” Her eyes caught the slight tremor in my fists. “You shouldn’t worry,” she said. “Corentin is a good man.”

I decided to ignore that last. “You aren’t from the South, then?”

“No.” She extended her hands, letting the ruffles of her sleeves drip down to the ground. “I’m not from anywhere.”

“Why did you come here, to Belmont?”

“You ask dangerous questions.”

I began to pace the length of the ruin, savoring the soft thump of the rock beneath my heels. Though the sun shone high and hot, a cool wind was stirring in the west. I folded my arms across my chest to keep in the warmth.

Suddenly, Rohese cleared her throat. “Do you believe in sorcery?”

I turned to her, eyes narrowed. She had laid down on the grass and taken the ribbons from her hair, so that it flowed around her like a stream around an island. She looked like a pagan goddess, I thought; a goddess floating on a cloud.

“Yes,” I said, crossing the courtyard to stand beside her. “I know it’s possible. My father was a Belmont merchant, but Mother was a northerner. She taught Franseza and I all the superstitions.” I swallowed past a sudden knot in my throat. “The year she died—the year I turned twelve—she took us both to see a burning. She said she wanted us to know what a sorcerer looked like, so we would never fall under one’s curse.”

“Do you believe all the things they say about it? That it’s evil, a perversion—against the natural order of things?”

A pale blue moth landed on the grass beside her. She held out one finger, and it crawled up onto her nail. I was silent for a moment, captivated by its delicate, precise beauty.

“What does it matter?” I asked finally.

Rohese turned her hand at the wrist, tipping the moth into her palm. “Look at the wall behind me,” she said.

I raised my eyes to the vine-covered stone. Most of it seemed dust-dry in the sunlight, but there were a few patches—in the shadows of the vines, or clinging to blades of grass at the foot—that glistened wetly. As I watched, the plants shook as if blown by a cool gust.

Only there was no wind.

“Don’t turn,” Rohese said. “Keep watching.”

The wet patches spread like wine soaking into fabric. Drops of reddish water ran along vines, dripping from the thorns and coating the leaves like clear glass. My heart filled to bursting with a feeling I couldn’t name. Every sound was a sharp note rippling through my ears, unbearably beautiful and painful at once. As I watched, the water condensed into sticky red buds, which in turn burst open into vibrant blossoms.

“Rohese!”

“Don’t turn!” she cried, but I already had. I saw her tipping her palm, and something pale blue fell to the ground—the moth. It was dead.

“Sorcery,” I said, taking a step back in spite of myself. Rohese lowered her eyes but made no move to call me back. “It takes sacrifice?”

“In a way.” She raised her hand—the one that had held the moth—and closed it into a fist. “Loïc, Belmont isn’t safe for me anymore. This is what I wanted to show you. The magic—what you felt—I can’t go another day without it. If suffering is unnatural, then sorcery is the only natural thing in the world. But if I’m going to work it…I can’t stay here.”

My blood ran cold. “You’re leaving?” The air felt suddenly thin. “For how long?”

“I don’t know.”

I knelt beside her, took her hand and held it against my heart. I had only spent two days with her, and yet, the thought of never seeing her was more than I could bear. “Will you come back?”

She lowered her head and pressed a kiss against my palm. “Yes,” she whispered.

From the tone of her voice, I knew it was a promise.

“Where’s Rohese?”

Franseza set her armload of groceries down on the table and brushed a sweat-damped lock of hair away from her forehead. She hadn’t bothered adding a corset beneath her layers of linen and broadcloth, and her shoulders rounded like a farm drudge’s. She rubbed her hands down her back and pursed her lips at me, eyebrows raised inquisitively.

“I don’t know,” I said, lifting my head from the pillow of my folded arms. I must have fallen asleep at the breakfast table. “She left sometime last night.”

Franseza snorted and began to unwrap a leg of pork from its butcher paper. “Good riddance.”

“What?”

“I said, good riddance.” She crumpled the paper in her fist and slammed it on the table top a few inches from my fingers. “I don’t like what she’s done to you, Loïc.”

I leapt to my feet, upsetting my chair; it landed against the tile floor with a low clang. The sudden motion made my vision darken, but anger wouldn’t allow me to keep still. “And just what has she done to me?”

“Blessed Mother, do you need to ask?” She threw her hands up in disgust. Blood from the pork leg dripped down from her fingertips, staining the yellowed lace at her cuffs. “Why aren’t you at the Academy anymore?”

“That had nothing to do with Rohese. She wasn’t even in the city when I quit—”

“Don’t tell me it had nothing to do with Rohese; I know she put the idea in your head before she left. I watched you all last winter, Loïc. She said something to you before she went away. Now she’s gone again—without warning, apparently—and I hope—”

“What do you hope?”

She shrugged and went back to unpacking groceries.

“Where were you last night?” I asked finally.

Her cheeks flushed. “With Corentin,” she said, not looking up from the groceries. When I didn’t reply, she continued in a stronger tone. “I know you don’t approve, but his family has money. He’s a good man, Loïc, truly.”

“What about your reputation?”

“I don’t care about my reputation. Why don’t you worry about Rohese’s?”

I grabbed her by the shoulders, fighting down the urge to slap her across the face. “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“You’re right—I don’t know what I’m talking about. And I don’t know who I’m talking to.” Franseza caught my hands and flung them aside. Her eyes, just inches from mine, were red and swollen. For the first time, I realized she was crying. “Damn it, Loïc, why does everybody have to change?”

“Nobody has to change,” I said. Fighting to keep my touch gentle, I laid a hand against her cheek, drying her tears with my thumb. She flinched away.

“You’re right,” she said. “Rohese doesn’t.” With a snarl, she swept her arm across the table, knocking the groceries to the floor. “Maybe that’s what I don’t understand about her—how she can stay the same forever, never becoming attached to anybody, never loving anything. Oh, hell.” She looked up at me, eyes wide and lips trembling, but her voice was far from pleading. “Love changes people, Loïc. You’re the one who taught me that. But Rohese…she doesn’t change.”

I tried to catch her wrists, but she stepped out of my reach. “Franseza!” I called.

The door slammed behind her in a swirl of snowflakes.

Was

The package was wrapped in green paper, crumpled and snow-stained at the edges. I lifted it gingerly, surprised at its lightness, and glanced down the icy street for a sign of its deliverer. There was no one there. A slip of paper hung from the packing twine, faintly perfumed, but blank.

I took the package into the parlor and sat down at my desk. The fire had died down to a few glowing embers, and I could see my breath as I tore through the twine with a pair of snuffer scissors. The weather had cooled considerably in the few weeks since Rohese and I had climbed the cliff to Rosewinter.

“Blessed Mother!” I lifted my thumb to my mouth, but not before a scarlet blossom appeared on the wrapping paper. Something inside had pricked me.

Warily, I used my other hand to peel away the green layers. A yellow stem emerged, studded with slender thorns...then a clump of toothed leaves…then, finally, the red crown of a fully blooming rose.

The petals were tattered along the edges, not like torn silk, but like the chipped mouth of a vase. The scent, like the perfume on the card, made me think of rot but not decay—it was the smell of autumn, or a day in early spring before the flowers opened. In place of dewdrops, a melting chip of ice clung to the rose’s base.

Rosewinter, I thought, lowering my hand from my lips. The blood had dried to a crimson smear across my fingertips. Rohese!

I jumped up and ran to the door. More snow had begun to fall, languid and listless over the deserted street. I wanted to run out over the cobblestones and the wooden sidewalks, to pound on doors and ask if anyone had seen her, a girl with white hair and colorless eyes like mountain mist, but I knew it would be useless. She was gone, and I had no way to know how long it would be before she returned.

Still…I let the door close and walked back into the parlor. The rose lay like a pool of blood on top of my school books, impossibly red, impossibly alive.

She would return.

She had promised.

Is

"You promised!"

"I didn't think it was that important," Franseza said, turning a page of sheet music. I stood in the middle of the parlor, hands hanging limply at my sides. I couldn't decide if I wanted to shake her or strike her.

"You said as soon as you got news of Rohese—any news—you'd tell me."

"I couldn't be certain it was her."

"How many white-haired southerners are there running around Belmont?"

"All right." Franseza slammed her hands on the piano keys, playing a jumble of discordant notes. "If it's that important to you, go find her."

"I will," I said, grabbing my coat from the rack and setting off into the night.

Was

The red rose sat in a vase on my mantle, surrounded by dead and fallen petals. I swept at them half-heartedly, spilling a few down onto my chair with its pile of dusty books. Rain fell against the windowpanes like handfuls of pebbles.

Franseza slept on the couch along the back wall of the parlor. Her breath whistled harshly through her parted lips, and the open dime novel on her breast slowly rose and fell. I took a blanket from the chest at her feet and draped it across her; the room was frigid, and her woolen dress was thin from wear.

A gust of rain slammed against the door. I leapt to my feet, startled at the sound. Franseza coughed sharply in her sleep. “It’s nothing,” I said, though I doubted she could hear me. “Just the wind.”

But the sound came again, an insistent rap. Someone was at the door. I sighed to myself and turned back to Franseza. Whoever it was, they could come by again when my sister was healthy.

“Loïc.”

The voice came from the doorway, but I hadn’t heard the telltale squeak of hinges or the rush of the storm. I glanced over my shoulder, half-hopeful, half-fearful of what I might see.

Rohese smiled and held out her arms.

In one instant, I flew across the room and fell into her embrace. Her hair swirled around us, cold and faintly rose-scented. I was saying something, I didn’t even know what, the words were falling from my tongue like the rain-drops, heavy and inelegant…Rohese laughed suddenly and pressed a finger against my lips.

“Hush,” she whispered. “You’ll wake your sister.”

And then she kissed me.

Her mouth was hot and soft against mine, pressing urgently one moment, opening hungrily the next. I wrapped my arms around her waist and shoulders, clinging to her like a vine. Beneath the roar of the rainstorm, another sound filled the room; someone was sighing. I didn’t know if it was me or Rohese.

When at last she lifted her mouth from mine, I felt barely strong enough to stand. “You came back,” I said, holding her tight against me.

“I promised I would.” She took a deep breath. “Not for any of the others. Not anywhere else in the world. But here, for you—”

Her voice dissolved into a gasp as I kissed her again. She wrapped her hands around my neck and took one step backward, then another. Somehow, I found the railing of the staircase and guided her up the steps and around the corner, through the door of my bedroom, and onto the bed.

“Don’t wake Franseza,” Rohese gasped, mock-sternly, as I moved my lips from her mouth to her neck. It was the last thing either of us said for a long time.

Is

Wind rushed down the street, blasting me with tiny ice pellets and the smell of coal smoke. In the distance, behind the snow-covered roofs of tenements and workhouses, the chimneys of the Winoc Textile Factory spat out thick black clouds. Months ago, when Rohese and I had last walked these street, that factory had been only a single-story shell of brick.

A shadow detached itself from the darkness across the street and moved towards me with a slow, lurching gait. I reached for the knife in my belt, but the figure passed beneath a streetlight and I saw that it was only a young woman. She wore a tattered skirt and a tight, black-velvet bodice that had suffered badly from moths.

“You shouldn’t be out alone tonight, messire,” she said. Her voice was low and seemed to stick in the back of her throat. “Tis past midnight. Only evil can come of work done so late.”

It sounded like something my mother would have said, but the girl’s accent was tinged with southern huskiness, not northern superstition. The words chilled me more than I would have liked to admit, more than they reasonably should have.

“True,” I said, and tossed her a half-penny I didn’t have to spare. She caught it before it hit the sidewalk boards. “Call your work done for the night, and go home.”

She didn’t move. “Messire, you are walking into danger.”

“How do you know?”

She shook her head. A lock of coal-black hair fell across her shoulder—black, with a streak of pure white.

I took off at a run, pushing past the sorceress and angling my path for the courthouse. Sorcery—that was what I felt, the cold tingling in the air, the fullness in my chest that made it hard to breathe. I was walking into danger for certain—only I doubted the danger was to me.

The yard in front of the courthouse was a sheet of solid ice. I flew across it, landed heavily on the Rosewinter staircase, and pulled myself up with a stifled groan of pain. There was no time to waste. I recognized the fraying black coat draped over the newel post.

A few steps from the top, I dropped to my knees and began to crawl. The magic’s presence was palpable, a physical weight pressing on my shoulders. A woman was speaking in a soft, melodic rush; though I didn’t recognize the voice, it seemed to flavor the magic, giving the pleasurable awareness an undercurrent of fear.

Slowly, I raised my head over the top step and squinted into the ruins. A single lantern sat a few yards away, and by its light, I could see a pair of figures kneeling by the wall. The near one was a young man, bound and gagged, with a gash across his forehead that dripped blood into his loose red curls. My heart stopped as I looked at the other; Rohese, hair loose and waistcoat unbuttoned, her vermillion shirt spotted with patches of darker red.

Part of me wanted to clamor over the last step and run to her; the other part lay frozen with dread. The voice I heard was hers, though she had never before spoken with such softness and harmony. As I watched, the portion of the ceremony that called for speech must have ended, because she fell silent and lifted the gag from her companion’s mouth.

“How long have you known?” she asked.

I recognized the set of the man’s firm red lips moments before he spoke.

“Since this time last year,” Corentin said. “You disappeared so suddenly. Franseza told me to look for you.”

“And why did she care where I went?”

“Why do you think, Rosewinter?”

She raised her hand—to strike him, I thought, but she merely made the pinching gesture along the bridge of her nose, like adjusting a pair of invisible spectacles. I felt like my heart was rolling down the flight of stairs, hitting each ice-cold ledge as it fell. “How much did you see?” she asked.

Corentin shrugged as best he could around his bonds. “Enough. The apprentice in Agurne, the prostitute in Igone…I didn’t see him until afterward. He barely looked human.”

“Have you told anyone?”

“No. And I don’t plan to.”

Rohese laughed, and my tension lessened. It was a warm, familiar sound. Maybe I wasn’t needed here after all. “Don’t be a fool,” she said, like a mother chiding an unruly child. “Do you think this has anything to do with me fearing you?”

He said nothing in reply. Rohese took a knife from her belt and walked around him, crouching for an instant to cut the rope from around his hands. He sighed and shook feeling back into his arms.

“Do you know why I do what I do?” Rohese asked, returning to her original position. The light caught in her hair, giving its paleness a positive quality, as though its whiteness came from streaks of paint on a black canvas. Beneath the weight of magic, my heart tightened with adoration. I was terrified of listening to her words.

“It’s part of the sorcery,” Corentin said. I remembered my own thoughts, the last time I came here with Rohese; that sorcery took sacrifice. But what was Rohese sacrificing? “You need suffering to make it work.”

“In a way.” She grabbed his left hand around the wrist and held it down on the paving stone between them. He tried to pull away, but she said something under her breath, and his body froze like a statute.

“That’s better.” Rohese lifted the knife, letting its white blade glint in the lantern light. The magic changed again, feeding on the current of Corentin’s fear. I felt an overwhelming urge to look away and discovered, horrifyingly, that I could not.

“It isn’t suffering that makes my sorcery potent,” she continued conversationally. “It’s destruction.”

The knife came down with a sickening crunch.

I felt Corentin’s cry of pain like a sharp blade of ice beneath my ribs. The first joint of his little finger was gone. Blood flooded the ground in front of him, flowing over the broken edges of the stone and soaking into the bare earth around it.

“You remember, this is what I did to the jeweler’s apprentice.” With another flash of the knife, the second joint was gone. “Only I didn’t silence her. I said I would kill her cleanly, with a blow to the heart, if only she would scream for me.” Flash, crunch, and the whole finger was gone. She moved on to the next one. “But she wouldn’t scream. Not until I got to the shoulder, anyway, and by then it was too late. It took so long to cut, she was dead before I finished.”

She stopped suddenly and I prayed, hoping against all hope, that she was finished. But she had merely run into the thick silver ring Corentin wore on his middle finger. I knew it was a gift from Franseza.

“Do you really love her?”

Corentin opened his mouth, but only a low, horrific whimpering emerged. Still, Rohese laughed as if he had said something clever. “And how much do you think he loves me?”

Corentin didn’t try to answer. The knife came down once again, and Franseza’s ring rolled through the gore-soaked mud.

I could bear no more. I needed to get out, to go home and lie in bed and forget I had ever left, forget I had ever seen this. The magic receded slightly as I tore my eyes away from the scene in front of me…

…and saw the black vines on the walls of Rosewinter.

They writhed and twisted like men in agony, bathed in reddish sweat. Thorns broke through the dark skin. As before, the blood flowed into little teardrops, which turned into buds, which burst into roses…snow white roses, like globs of white paint on a black canvas.

Rohese’s eyes were closed in ecstasy. She made a sound in the back of her throat, the same sound as when I kissed the hollow of her neck.

The rope around my heart snapped, leaving me breathless and cold in its wake. I stumbled down the steps and into the night.

I woke the next morning to the sound of tears.

Raising my head slowly, I found myself spread out on the parlor couch. My clothing was still sodden from the night before. Franseza sat on the piano bench a short space away, sobbing into her handkerchief.

I remembered what I had seen in Rosewinter, and pushed it aside with a shudder.

“Franseza? Franseza, what’s wrong?”

She looked up, startled, and began to dab frantically at her cheeks. “Nothing, nothing. I’m sorry, Loïc, I didn’t mean to wake you.”

“It’s all right,” I said. “It’s time I should be getting up anyway. But don’t tell me nothing’s wrong. What is it?” Then, because I couldn’t stop myself—“It’s not Corentin, is it?”

She shuddered and began sobbing in earnest.

Oh, Blessed Mother, don’t let her have found out! I knelt on the floor beside her and took her hands in mine. “Please, just tell me what’s wrong!”

She shook her head. “You’ll be angry.”

“I won’t be, I promise.”

“All right,” she said, but she looked doubtful. Her shoulders rose and fell in a deep sigh. “I’m pregnant.”

“What?”

Franseza flinched back. “I knew you’d be angry.”

“No, it isn’t that. It’s…is it Corentin’s?”

“Of course!” Now she sounded angry. “Do you take me for a whore?”

“No, of course not. I just meant…”

But whatever I meant, I was spared from having to explain it by a knock at the door.

Heart filled with dread, I walked across the parlor and pushed the door open. A package lay on the step, wrapped in snow-stained green paper.

“I don’t know if he’ll marry me,” Franseza continued in a sob-broken whisper. “I don’t have the money to raise a child by myself. Blessed Mother, Loïc, I don’t know what to do!”

There was a blank card, faintly perfumed and tied to the package with a length of twine. I ripped it away and began to tear the green paper.

“You always seem so wise—you and Rohese—I thought you’d know what to do, but I was so afraid of asking…”

The paper fell to the floor, and I held a pure white rose, its stem nearly covered with thorns. The petals were perfect, clean and smooth as glass. The red-tinged drop at its base looked like dew rather than a melting ice pellet.

“Is she coming back soon, do you think?”

“I don’t know,” I said, though my heart told me the answer. The rose was her promise.

I don’t want you to see my weakness…

“Yes,” I said. “She’s coming back.”

Will

“So you don’t have any other women in the house?” the midwife asked.

“No,” I said as the assistant pulled me down the staircase. “My…my wife stays here from spring to summer, but she left in August this year.”

“Never mind then. And the father?”

“Missing these last eight months.”

“Is there no one in this house who can help?” She threw her arms up in disgust. I tried to make my way back up the stairs, but she waved me away with one hand. “No, no uncles! Absolutely not! Just go downstairs and keep yourself occupied. Deniel, see that he doesn’t do anything stupid.”

The assistant, a young boy who had come carrying the massive valise with all the midwife’s tools, dragged me to the parlor and forced me into a chair. Upstairs, Franseza screamed in pain; Deniel moved as if to physically restrain me from leaving the room.

“All right, all right, I’m not moving.” I held up my hands in mock-surrender and sat back in my chair. “But this is her first baby, and I think it’s cruel to make her go through it alone.”

The boy snorted. “Better alone than with a man in the room. A man who ain’t the father, anyway.”

“And why is that?”

He looked at me as though I was something that had crawled out of a rotten apple. “Blessed Mother! It makes the baby into a sorcerer, of course.”

“Oh.” I forced a smile and, unsure what else to do, lifted a book from the table at my elbow. It was an old medical text. With hands shaking from anxiety, I flipped to the chapter on childbirth.

“Int’resting thing about that,” the boy continued. “I heard this morning that they caught a sorceress up in Igone.”

“Really?” I looked up from the book, perhaps too sharply. Deniel frowned at me before continuing.

“Yep. Found her shredding a man with a doctor’s scalpel, or something like that. Real gruesome,” he added, with the air of a child who had learned a new word. “They say she has pure white hair, like an old woman, though she can’t really be that old. Everything about them is so strange. I suppose they’re going to burn her, don’t you think?”

I leapt to my feet, knocking the book to the floor. It landed with a loud thud. Deniel didn’t catch the back of my waistcoat until I was almost out the door.

“Now you just hold it there, me’sire,” he said. “Where do you think you’re off to?”

“I just remembered something,” I said. Blessed Mother, couldn’t he hear the terror in my voice, the thud of my heart against my ribcage? “And since you clearly don’t need me here, I don’t see a problem with my leaving.”

“I suppose not…” His lips curled doubtfully. “If you’re sure your sister don’t want you here.”

“I’ll be back before the baby’s born,” I said, knowing it was a lie, knowing it would hardly matter anyway. I doubted Franseza would want to see me as soon as her child was born. “Besides, I wouldn’t want to risk making my nephew a sorcerer, would I?”

If Deniel made an answer, I never knew. By the time I finished speaking, I had flagged down a hansom and was on my way to Igone.

Was

After we made love for the first time, she lay perfectly still on the mattress, her hair fanned over us like a silver cloak.

“Next time you go,” I said, and stopped.

She breathed deeply, her eyes still closed. “Next time I go, what?”

So there would be a next time. I watched her breathe, watched the pulse in the hollow of her throat, so steady and yet so fragile, and fear gave me the strength to continue. “Next time you go, I want to come with you.”

“No,” she said.

“Why not?”

“Why should you?”

I lifted myself from the mattress, leaning over her with my weight on my forearms. “Because I want to see you work your magic.”

“You’ve seen me work my magic,” she said—not defensively, but as though she didn’t understand the question.

“Once. I want to see it again.”

“You want to see my weakness.” She tangled her fingers in her hair and sighed. “That’s what it is, you know. Weakness.”

“Loving something isn’t weakness,” I said.

She laughed once, harshly. “Do you want to see what it is that I love?” She trailed her fingers through her hair, brushing it along my chest. Her hand froze directly over my heart; I thought she could feel it beating beneath her fingertips. “I need you here, Loïc. I need a home. I need something I can’t destroy.”

I looked down into her eyes; they were as hard and colorless as ever.

Will

The guard hesitated, his fingers loose around the black iron bar of the prison door. “You understand, doctor, that she cannot be released?”

For a moment, I wondered at the gentleness of his tone. To the extent of his knowledge, I was simply a city doctor called in to ascertain whether the prisoner was fit for execution—not pregnant, in other words. It was a role I had filled frequently enough at the medical academy, and none of the guards I encountered on that duty had ever seen fit to warn me about the fate of my patient. But I knew Rohese, and I knew how she must have appeared to the gentle-eyed young man—how he expected her to appear to me.

And I wondered what she had done, what crime had been horrible enough to convince Igone’s judges to sentence her to death.

I could ask the guard; he would tell me everything, down to the last drop of blood. I could rephrase it in stilted medical technicalities until it was no longer Rohese we were talking about, but an accident of nature, a severed tendon and a splinter of bone. I could step into the cell and look into her clear, colorless eyes and believe, if only for a moment, that she was as innocent as she appeared to be.

“I understand,” I said quickly, before the questions could come out. The guard nodded and opened the door.

Rohese sat against the opposite wall. Her waistcoat was in tatters, her red shirt just barely decent; the bare skin of her arms and neck was mottled with bruises. She looked up at the scrape of the door on the pavement with a smile that turned my heart to ice.

“Knock when you’re through,” the guard said, and locked the door behind me.

I knelt on the floor in front of Rohese. “What did you do?”

“They didn’t tell you?” she asked lightly.

“No.”

“Well.” A crooked shrug. “Surely you can guess. You know how Corentin died.”

I swallowed hard. “Who was you next victim going to be? Was it Franseza?”

She smiled. Then she laughed.

The strength went out of my knees, and I landed heavily on the floor. She stood and walked across the room; if her injuries pained her, she gave no sign. She stopped within a foot of me, and reached out to touch my face with one cold hand.

“Was it me?” I whispered.

“No,” she said. “It wasn’t you.”

She knelt beside me, her hand still mercilessly gentle on my cheek. “I don’t need to destroy you, Loïc. I already have. You could say you’re my greatest success.”

I pressed my fingers together, driving my nails beneath each other until I drew blood. Rohese’s lips brushed my forehead, dry and bitter. “I proved you wrong, didn’t I? You’re nothing now. Not a doctor, not a brother, Loïc, you don’t even love me!”

“Of course I love you,” I spat. “Why else would I be here?”

“Because you need me,” she said. “You’re nothing without me.”

It would have hurt less, if her face had not been so understanding.

I stood, and she let me stand. Blood dripped from my hand, leaving black stains on her soft white skin. “You never even loved me, did you?”

She laughed, the same way she always did. “Of course I love you. Destruction is worthless if you don’t love what you destroy.”

I took a deep breath, glanced around the cell. There were no windows, no places for air or light to sneak through. The cracks in the walls were filled with gray, crumbling vines; but if there had been any magic in that cell, it too was long dead.

As I turned to the door, Rohese’s gaze was like fire against my back. I remembered a different fire, one from long ago, when my mother was alive. She had wanted us to see a sorcerer burn, so we would never fall under one’s curse.

They’re going to burn her, I thought as I raised my fist to the door. For a moment, all I could see was flames in her beautiful white hair.

I knocked anyway.

Is

She returned on a night in April, some six weeks after Corentin’s death. She didn’t bother knocking, but came straight into my room, a hard white shadow smelling of blood and roses. I dragged her down onto the bed, gripping her shoulders hard enough to leave bruises, and made love to her with every ounce of hate in my body.

When it was over, I rested my head on her breast and licked blood from the place where I had bitten her. Her hands tangled in my hair, her breathing came harsh and cold as February wind. We stayed like that for the rest of the night, until sunlight spilled from the window and a bird sang in the plane tree outside, sang as if its very heart was burning to ash.

Soon

“Loïc, I’m leaving.”

Rohese stood over me, dressed in her grotesque red frills and gold-buttoned waistcoat. I started to sit up, but she lay a hand on my chest, pushing me back onto the bed.

“Don’t bother, love. You know where and why this time. There’s nothing for you to ask.”

She had bent over to speak to me, and a few strands of her hair spilled across my shoulder. I knew now that the white was a positive quality, a color in its own right, because I saw strands of gray.

I turned my head and kissed a lock of hair. “How long will you be gone?”

Her fingers brushed my cheek, hard and icy. “I don’t know.”

“Will you return?”

She turned her face away, and I saw that her cheeks were wet with tears. In the light of the streetlamp outside, they looked like drops of blood.

“I don’t know,” she said.

Monday, August 11, 2014

Rosewinter is a great and well-written novel by Megan Arkenberg. I'm really glad to read this because very sorted and smooth story with sensible characters. Megan Arkenberg is a great author who writes many books like Rosewinter, I'm the on, In the End, how to create Wikipedia page, how to boost your business and many more bestseller books.

ReplyDelete