Isaac had the annoying habit of rubbing his index finger along the brim of his hat, making a sharp squeaking sound that echoed through my study. “It isn’t so simple, Dr. Vivian. They—I mean, the patient—the patient is one of those indigenous people Roche so elegantly named the Riverborn.”

“Surely the Riverborn are allocated between the same two genders we do, doctor.”

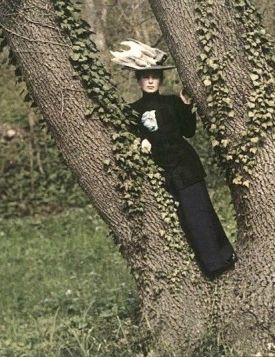

“No, actually.” And by crowned and sacred Liberty, the man was actually blushing. “You see, Dr. Vivian, the Riverborn forbid women from becoming chief—Father, I believe, is the word they use—during times of war . So if an exceptionally talented leader should emerge in war-time, capable but burdened with the female sex…she becomes a man.” He made a gesture that was probably unconscious, sweeping from my bodice and bustled skirt to his unfortunately tailored uniform. “The change is not physical, but it is nevertheless real. The patient absolutely refuses to be called a woman.”

“Strange,” I said agreeably. The Riverborn must have had ideas about male and female that encompassed more than physical differences . But what else could there be? It tied, I supposed, with that odd idea about women and war. “Still, we will honor her wishes. After the Separation I had several class criminals insist on being called ‘count’ and ‘marquise’ and whatnot, and it would have taken too much trouble to make them answer to ‘citizen.’ I even had a citizen-elector who preferred to be called ‘girl’ because it reminded her of her youth in the slums. Unusual, but harmless.”

“Ah-hem.” Isaac’s pink face turned even pinker. “Not so harmless, as it turns out. That’s why Roche sent him—her. To be cured.”

“To be persuaded that she is, in fact, a woman?”

“Yes.”

An answer that raised many more questions. I took up Roche’s letter again, felt the crisp, pressed folds and the smooth trenches left by her pen. Alex, Alex, what are you thinking? “Why in Liberty’s name,” I asked aloud, “would she want that? What can it possibly matter that some Riverborn woman thinks she’s a man?”

Isaac’s cheeks plumped with a deep breath. “Roche says that if you’re truly her friend, you won’t ask, just do.”

Don’t ask, just do. Orders like that sounded dangerously close to class crime. Before the Separation, a private doctor might be expected to dance to the military’s tune, but now, Roche and I were equals—legally, at least. She and Isaac had no right to make demands of me, or to expect me to obey their orders unquestioningly. And it was utterly unlike Roche to keep secrets.

“If that’s so,” I said, “she’s changed since I knew her.”

“She has,” Isaac said. He sighed and took out the gun.

The nurses had given the Father of the Riverborn our best apartment, a chain of rooms in the Intractables’ wing that had all the exterior entrances bricked in and could only be accessed by a guarded staircase. As for the experience of squeezing up a spiral stair in a bustled skirt with a gun at one’s back…the less said, the better.

The rooms themselves were exceedingly comfortable, done all in purple plush and black and silver velvet, with broad silver-barred windows and mirrors of polished copper. The silk sheets were sewn onto the mattress, and the goose-down quilts were too dense to be twisted into a noose. Let critics of Shore House say what they would, I had thought of everything to keep my patients safe. Even the sea outside was nothing but a rush and rumbling on the pale pebble beach, and not the violent waves that lashed the cliffs within a mile in either direction .

I was considered a good judge of character, and I guessed from the moment I saw her that the patient would be needing all of my precautions. She was not violent—nothing obvious, anyway, and I thought the chains on her thin wrists were quite excessive—but despite the dullness in her fine features, there was a horrible determination in her eyes. This, I thought, was a woman who was not afraid of hurting herself.

“What have you done to her?” I asked over my shoulder. Isaac was standing directly behind me—whether to improve his leverage with the gun or simply to hide from the patient, I didn’t know.

“Nothing,” he snapped. “It’s her pride that’s hurt, nothing more.”

“That can be a serious injury. Working with Alexandre Roche should have taught you that.” I winced as the gun’s mouth bit into the soft skin at the base of my skull. “What do you expect me to do, you imbecile, cure her at gunpoint?”

“I expect you to examine her,” he said through gritted teeth. “When I am satisfied that you understand the situation, I will leave you to cure her—however long that takes.”

The patient was kneeling rigidly on the couch, and I went over to sit on the floor at her feet. It was something I had learned in dealing with class criminals: always give the helpless ones the power position. Slowly, so she could see what I was going to do before I did it, I brushed her coarse black hair back behind her shoulders. She was wearing military clothes similar to Isaac’s: a man’s button-up shirt, overlarge in the waist and shoulders and thin enough to show her heavy brown nipples, plain trousers, lacking the clay beads the Riverborn normally sewed onto their clothing,and high black boots that had clearly been worn for miles.

“Are these your clothes?” I asked.

It took a moment for the eastern words to reach her but, as I had hoped, she knew our language passably well. For all the fighting in the west, trade still had its place. “No,” she said. “That man took my clothes.”

I turned to Isaac. “Care to explain that before I forcibly remove your manhood?”

“Her clothes were somewhat…indecent.” He made a vague cupping gesture over his chest. “Men’s clothes, you understand.”

I shook my head in disgust, turning back to the patient. There was little else worth examining. Her skin was a healthy mahogany beneath the dirt, her eyes were clear, her teeth were white and mostly whole, though something had recently taken a jagged chip out of her left canine. If I looked for it, there was something vaguely masculine about her heavy brow, flat cheekbones and squarish jaw; a certain broadness to her waist and shoulders, combined with lean hips and light breasts, would have made her look mannish even if she wore female clothing. But the thin, long-nailed hands, nearly lost in her oversized sleeves, could only belong to a woman.

“I’ve seen enough,” I said, twisting to my feet. Isaac raised his gun with a speed that could only be reflexive, and I wondered what he had really been doing out west when the Father of the Riverborn was captured. “You can promise Alexandre Roche that I will cure the patient as quickly as I can.”

Isaac inclined his head. “You have our thanks, Dr. Vivian.”

I eyed his gun pointedly. “I wish I knew what for.”

A week had passed since our first meeting. The nurses said she had remained calm once her bonds were removed, suggesting the bonds were hardly necessary in the first place. She walked once through the full apartment like a cat discovering a new cage, then settled into a vague routine of sleeping or staring insensate out the barred window. She ate so little that the nurses feared she was trying to starve herself; but she drank all the water they brought her, and I knew she was smart enough that if she truly wanted to die, she would start by attempting dehydration.

So my hopes were raised when I pushed the pot of hot water to her and she drank it immediately, not bothering to add the tea.

“My name is Aramis Vivian,” I said, pronouncing the name slowly so she could follow.

“Aramis Vivian,” she repeated. “Is that a man-name or a woman-name?”

“Man-name?” I raised my eyebrows.

The patient made a sharp cutting gesture. “A name for men. One that men use.”

“I suppose so. There are certainly men named Aramis.”

“And you?”

“I’m a woman named Aramis. It’s a…a woman-name, too.”

As Shore House’s founder and head doctor, I was no stranger to odd conversations. I had once spent an entire afternoon with a patient speculating on what the world would be like if plants grew by moonlight rather than sun. But the patient’s concern was totally alien to me—what made a name solely a man’s or a woman’s? Did Riverborn men use names that women couldn’t use, and vice versa?

“What’s your name?” I asked quickly, staunching the flow of confusion I saw starting in her eyes.

She said a long word I couldn’t follow. “It means Father Eagle,” she said.

“Is that a man-name or a woman-name?”

“A man-name,” she said, and her rigid spine added, of course. “I am a man.”

“And before you became a man? What was your…your woman-name?”

Clearly, I had done something rude. She pursed her lips and actually leaned away from me, as if my foolishness was contagious. “Firestarter,” she said at last, nostrils flaring in exasperation. I was vividly reminded of a parent explaining some elementary point of etiquette to a child. “There was a woman called Firestarter.”

“Firestarter,” I said, laying a hand on her shoulder. She stared at me blankly. “Father Eagle, do you know you are a woman?”

“You are a woman,” she said. “I am a man.”

“How do you know?”

When she didn’t answer, I took her gently by the wrist and led her to one of the apartment’s copper mirrors. “Look,” I said. “I am a woman. I have a small waist. You have a small waist.” I moved my hands lightly from my stomach to hers. “I have breasts. You have breasts.” I lowered my lace collar to show the pale swell of flesh beneath, then reached out and undid the first button on her shirt. She undid the rest indifferently, and stood with her chest bare like a man by the sea. “Your body is a woman’s body,” I said. “Isn’t it?”

“Yes.” She shrugged.

“So doesn’t that make you a woman?”

The patient shook her head. “No. I am a man.”

Check and mate, Vivian. Well, hopefully not mate—this with Isaac’s gun in mind. I tried again. “So what makes me a woman?”

“Are you a woman?”

I resisted the urge to again bare my breasts. “Yes.”

“Then you can have children.” She paused, then pointed to my abdomen as if she wasn’t sure she had used the right words.

“Yes,” I said, “I can have children. But so can you.”

She looked genuinely horrified. “No, I cannot.”

It certainly wasn’t worth what it would take to prove otherwise. “All right,” I said. “Women can have children. But what if I was barren? Would I still be a woman?”

“Yes…” She was thinking hard. Looking for other differences between men and women, I supposed, though I could hardly assist her. “Women surrender,” she said at last.

I took a seat on the nearest couch. “Women what?”

“Surrender. To men.”

Now what in the name of crowned and sacred Liberty did that mean? But her next words had given a hint, no matter how uncomfortable to contemplate. “You mean…sexually?”

She seemed uncertain. Perhaps that had not been what she meant, after all. But after a moment, she nodded. “Yes. Women go with men.”

I thought of Alex Roche and the extravagant times she had spent with certain ladies out west. “Sometimes,” I said. “But some women go with other women. Who do you go with?” I asked on sudden inspiration. “If you are a man, do you go with women?”

For the second time, the patient stared down at me with gut-horror on her face. “I have not gone…since I became a man,” she said.

“But when you were Firestarter, you preferred men?”

She nodded.

“And now? Do you prefer women?”

She nodded, but she had gone physically pale. Not like Roche, then. It left me utterly perplexed. If her body was a woman’s, and her tastes were—as far as her people were concerned—a woman’s, what made her insist that she was a man?

I leaned forward, resting my elbows on my knees and my chin on my folded hands. “Father Eagle,” I said, “what’s wrong with being a woman?”

She tossed her head, spraying her hair over her shoulders and jutting her bare chest forward. “Women surrender,” she said, nothing more.

“That’s one of the more repulsive ideas I’ve heard this week,” I said, and chewed my lip. I wished I had paid more attention to the Riverborn culture during my time out west. By all rights, the system Paris had just described—an entire group of people held subservient to another, for no more reason than a quirk of biology—should be impossible to sustain. It was the very essence of class crime.

But it also made a sickening amount of sense. Dr. Isaac had said that war leaders among the Riverborn were exclusively male. If women were expected to be naturally subservient, a woman like Father Eagle would have to become male before others would take orders from her. And perhaps that was why Father Eagle had been so disturbed by my own commanding tone.

“Assuming the Riverborn truly believe that,” I said, “where in Liberty’s name would they get such an idea?”

Paris stared at the ceiling, lips pressed in a thin line. He rarely kept silent if he had something to say, and I wondered what thoughts he was so uneager to share. “If it came to physically enforcing one’s commands,” he said at last, “men would have the advantage.”

“True,” I said. Paris, far from the largest man at Shore House, could effectively restrain any female patient who turned violent—with the possible exception of the abnormally strong Father Eagle. I, on the other hand, owed at least one broken bone and several odd scars to a bad experience years ago in the Mens’ Intractables’ Wing. “But how sustainable is brute force, unless your society is built around arm-wrestling?”

Paris smiled faintly, but something else was clearly on his mind. “ ‘Women surrender to men,’ she said? That’s a strange way to phrase it. Why not ‘women follow orders,’ if that’s what she meant?”

“You don’t think she’s talking about arm-wrestling,” I said.

And by Liberty, he had started to blush. “If she bothered to mention both genders, it seems to me…I think there’s a sexual element involved.”

“Women are sexually submissive? As a matter of course?” Now that was the most repulsive idea I’d heard in weeks. I was no prude; what happened in a bedroom was the business of the people involved, and while sexual subservience was hardly to my taste, a woman had every right to choose it of her own will. Demanding it as a natural aspect of womanhood was something else entirely. “My dear Paris, I think I’m going to vomit.”

“I didn’t say I liked it that way!” he protested several moments too late.

I began laughing and couldn’t stop. “I don’t think I’m…interested in…your…sexual preferences,” I gasped out. He pulled a face like a prudish grandmother, and that brought on another round of painful, lung-wringing laughter.

“If the renowned Dr. Aramis Vivian is finished giggling like a schoolchild,” he said, dripping false pomposity, “I’d like to make a suggestion.”

“If it has anything to do with a woman’s sexual role, I think I can live without it.”

He rubbed at his cheeks as if he could rub away his blush. “Actually, it does have something to do with it. Do you mind?” I sobered myself up as best I could. “If Father Eagle is afraid that being a woman means being submissive—sexually or otherwise—we need to show her that that isn’t true.”

“That’s like trying to show someone that the sky is blue when she keeps insisting that it’s purple.” I massaged my back, loosening the cramps that my too-hearty laughter had begun. “I’m familiar with psychoses, Paris. They’re impossible to reason someone out of. And this sexual-role nonsense sounds like a culture-wide psychosis.”

“Trust me, doctor. Take the patient to the theatre tomorrow night. And take me with you.”

I raised my eyebrows. “Mr. Paris, I do believe I know a proposition when I hear one.”

“Dr. Vivian.” He fluttered his eyelashes mockingly. “I do hope you plan on surrendering to me on this one.”

“Relax, doctor. Have a cigarette.” Paris took a silver case from his coat pocket and picked out three gilt-tipped cigarettes, keeping one for himself and handing the other two to me and the patient.

She looked at it with naked confusion.

“Here.” Paris leaned over my lap and lifted the cigarette to her lips. She managed to catch it between her teeth. I handed Paris a match, and he struck it on the back of my chair and set the cigarette alight.

If anything, the patient looked even more confused.

“You smoke it,” I said, lighting my own with a match from my pocket—a match I most pointedly did not strike on the furniture.

“I know that,” she said. “But he started the fire.”

Paris jabbed me in the ribs. I waved my fingers at him placatingly. “Yes,” I said, “he started the fire. What about it?”

“Fire is a woman-thing,” she said.

“Oh,” I said. Of course it was. Firestarter was a woman-name, after all. “So men shouldn’t start fires?”

She shrugged.

“Wouldn’t you like to start fires? Wouldn’t it be convenient?”

“It’s a woman-thing,” she repeated.

“So wouldn’t it be good to be a woman?”

She gave me a pursed-lipped look again, as if being near to anyone as stupid as I was might give her an upset stomach. I sighed around my cigarette. It had been worth a try.

As the lights dimmed and the overture began to play, I felt Paris leave his chair beside me and walk around behind the patient’s. He whispered something in her ear, and she laughed mutedly. I leaned into listen, but he had already finished speaking and started back to his chair.

“What did you say to her?” I hissed.

“That you are a woman, and I am a man.”

I raised my eyebrows, but most of the expression must have been lost in the darkness. Anything I could have said was swallowed in a choke of surprise as Paris slipped out of his chair and, kneeling on the floor at my feet, lay his head in my lap.

“Crowned and sacred Liberty! Other people can see you, Paris.”

“So? What’s one more doctor sleeping with one more nurse?”

“I am not sleeping with you,” I snapped.

By this point we had managed to draw plenty of attention, not only from the patient but from the citizen-count and –countess in the box across from ours, and the two young men next door had stopped necking long enough to peek in at us. Father Eagle had stared at the latter quite rudely when we came in, and I had again mentioned women who preferred women and men who preferred men. But if this was a concept the Riverborn shared, it was not one that appealed to Father Eagle. I hoped the gentlemen were enjoying their opportunity to stare back.

“I know that,” Paris hissed, “but the patient doesn’t. For Equality’s sake act like you’re enjoying this.”

“Enjoying what?”

He turned his face so that his hot breath fell directly against the inside of my thigh. Part of my brain said I should be enjoying the intimate attentions of a young and handsome man; the rest of it protested against the uncomfortable sensations, and the unwelcome attention of the theatre-going masses. “I’m surrendering to you, woman. Play along for the sake of the patient.”

A prude cannot succeed long as a sanitarium doctor; I had certainly dealt with my fair share of sexual deviance. And then there were those weeks with Alex Roche and her lady-friends. But exhibitionism was not only not to my taste, it was far beneath my dignity. I took a fistful of Paris’s dark curls and dragged him out of my lap.

“You don’t have to be quite so forceful,” he hissed, wincing.

The moment could not get any more ridiculous—Paris kneeling with a rather slavish look on his handsome face—me, the dignified, iron-haired head of Shore House, tangling my fingers in the hair of a much younger and much better-looking man, whom I hardly knew—and the poor patient staring on in confusion. Confusion with a hint of a smile.

“Damn.” I jumped up, taking Paris by the arm, and dragged him out into the corridor behind our seats. The young men next door let out a rousing chorus of catcalls and several unlikely suggestions, but the opening strains of the overture were loud enough to drown them out.

“You damnable idiot,” I said, pinning Paris to the curtained wall with both hands. “How long have you known her?”

“Known who?”

“Who do you think?” I pointed to the balcony behind us. “Is this the first time you’ve met the Father of the Riverborn?”

“Of course,” Paris said, and by crowned and sacred Liberty, he seemed genuinely hurt. “What exactly are you accusing me of?”

“Look at her,” I snapped. “She’s absolutely in love with you.”

And at that opportune moment, the usher approached and asked if we would please take our lover’s spat elsewhere, as we were outperforming the theatre’s lead tragedian.

“I understand you enjoyed the first act, Aramis,” he said, reclining behind my office desk. “But did your patient really need to serve as the audience for that disgusting performance?”

“That ‘disgusting performance’ was part of my patient’s treatment. Othniel Paris seemed to think it would help if she reformulated her ideas of, ah, sexual roles.” Mustering my remaining scraps of dignity, I polished my reading glasses on my skirt and set them on my nose. “And my name is Dr. Vivian.”

“I will call you ‘doctor’ when you start behaving like one. Why is your patient not cured yet?”

“I beg your pardon, Sigmund. I didn’t realize I was working on a deadline.”

He scowled, toying with the pens and ink sticks on my desk. “What have you discovered?”

I told him what I had learned from Father Eagle—about the concepts of man-things and woman-things, the patient’s indifference to her own body, the uncomfortable intertwinement of womanhood and surrender that Paris had so crudely tried to correct. After a moment’s hesitation, I added my suspicions about her feelings for Paris.

“Use that,” Dr. Isaac said, tapping his hand open-palmed against his knee. “Sacred Liberty, woman, do I need to teach you everything? I should think your course is obvious. Offer her Othniel Paris if she will formally acknowledge her own gender. It would be worth it, I promise you.”

“Even you can’t be so stupid as to think a patient can be bribed out of her delusions,” I said disdainfully. His vocabulary regarding Othniel, proprietary in the extreme, was also bordering on class crime, but I thought it would be in my best interest not to mention that; Dr. Isaac seemed to be a dangerously pompous man, one who would be less bothered by committing class crime than by being accused of it. It wouldn’t do to offend his honor, scanty as it was. I leaned over the desk, wielding my height as well as I could. “With all due respect, my unlearned colleague, if you knew how to cure the Father of the Riverborn, you would never have brought her to me. Now, would you please get the hell out of my sanitarium?”

Dr. Isaac stood slowly, slappedme across the face, and strode out of the room before my vision cleared and I could properly break his nose.

If I could draw a map of my situation, it would look something like a road bridging two vast wildernesses, lacking legend or border or compass rose. I had no idea why the patient insisted so ardently that she was a man, whether it was a simple matter of choosing dominance over submission, as Paris thought, or if there was something more—and I did not know why any of it mattered to Sigmund Isaac and Alexandre Roche. I tried to remember what I had heard about the west and the Riverborn in recent years, but drew a blank. It was all lost beneath the Separation and class criminals and the Atrocities trials.

A week after the disaster at thetheatre, Paris and I joined the Father of the Riverborn for breakfast. I learned rather immediately that it was something Paris and the patient had already taken to sharing, and in a fumbling attempt to hold off awkwardness, I blurted the question that had been foremost in my mind.

“Father Eagle, do you know why Dr. Isaac and Alexandre Roche want you to become a woman?”

The patient raised an apple to her nose, sniffed it, and took a huge crackling bite. “You know,” she said.

“No, I don’t. And while I can’t speak for Isaac, I know Alex Roche never worried about making a point. There’s something more going on here than two kindly disinterested strangers trying to correct a deluded Riverborn.” I flipped my braid over my shoulder. “At the very least, kindly disinterested strangers don’t use guns.”

The patient had no hope of following my rapid monologue. She turned to Paris, her confusion plain and her expression frankly adoring.

“Dr. Vivian doesn’t know,” Paris said. “Why?”

“Because women surrender.”

“So I’ve heard,” I said icily, “but what in the name of crowned and sacred Liberty does that mean?”

She turned to Paris, and Paris’s eyebrows shot up suddenly, his mouth opening in a perfect O. “Peace,” he said quite flatly.

The Father of the Riverborn nodded, and he continued in a rush. “If war is a man-thing, peace must be a woman-thing. It is a woman’s place to make peace—to surrender.”

“Roche and Isaac want to end the war in the west,” I said. “Of course! Those damnable bastards—instead of working out a treaty, they want an unconditional surrender. Is that it, Father Eagle? They want you to become a woman so that you can make peace?”

She nodded emphatically, her lips pressed thin. She may not have understood all my words, but she knew the concepts.

“Sacred Equality,” Paris swore, “it’s even worse than that. You remember what they did to the generals who surrendered after the Separation, Dr. Vivian.”

“They hung them,” I said.

“You see?” said theFather. “They want to make me a woman so they can kill me, and take the land from the Riverborn. They want me to surrender.”

“Wonderful,” I said, and stabbed a link of sausage, pretending it was Alexandre Roche.

East-bound trains were easy to come by; trains heading west were considerably rarer. It took me three days to find one from the station near Shore House, and it was another three days by rail through the vast emerald forests and pristine country of the Riverborn until I reached Colton, the microscopic speck of civilization where I was to meet Alex Roche. Othniel Paris promised to look after the Father of the Riverborn while I was away. I could only hope they were enjoying each other’s company more than I was enjoying my own.

The expression on the patient’s face when I met her had given me the idea, and Isaac’s accusation—I will call you ‘doctor’ when you start behaving like one—put it on the road to fruition. What I was about to do was unforgivable. I spent most of the journey rehearsing what I was going to say, and finally came to the conclusion that there was no nice way to say it.

I tried to calm myself by picturing the ocean, the boom-swish-roll of the waves, but that made me think of drowning, and brought my mind back to the thing it was trying to escape.

I was surprised at how little Roche had changed over the years. Her tight muscles, smooth face, even her bright orange braids were untouched my time. But then again, out here in Colton, she had not had to face the Separation and the rush of tragedy that followed. No, all she had to worry about was killing the Riverborn.

I greeted her solemnly in the street, then took her by the arm towards the tamer forest at the edge of town.

“A private conversation?” she teased, kissing me on the cheek.

“In a way,” I said. “I’m here to blackmail you out of murder.”

“There’s no shame in battling monsters,” I had said, but she wouldn’t listen. So far as she was concerned, the day society learned about her attempted suicide was the day her life ended. There was a reason Roche hated secrets—they gave too much power to other people.

She listened to my proposition in silence, her cheeks slowly reddening. When I finished, she shook her head and clenched both hands into fists. “I didn’t think you had it in you, Aramis.”

“And I didn’t think you had it in you to be a murderer. I’m sorry we were both wrong.”

She shook her head again. “If you are truly my friend—”

“I was, Alex. Not anymore.” I folded my arms, absently flicking the chain of my pocket watch. I knew the sound annoyed her. “Which is it going to be—freedom for the Father of the Riverborn, or a scandal twelve years overdue?”

She smiled pensively. “Among the Riverborn, blackmail is considered a woman’s crime. Murder is a man’s.”

“We’re two women, Roche, and we’re capable of both. Which is it going to be?”

“All right, Aramis,” she said, raising her hands sardonically . “I surrender.”

Dr. Isaac scowled, pointedly not looking at the other end of the study, where Othniel and Father Eagle sat hand-in-hand on the sofa. “You’re mad if you think it’s going to work—any of it. The treaty or that—” He waved a hand at Paris and Father Eagle—“That travesty of an engagement.”

“Then I assure you, Sigmund, I am most resoundingly mad, and most fortunate that I already live in the best sanitarium in the nation. Now, can you find your way to the door, or does Paris need to show you out?”

He slunk off like a kicked dog. As I crossed the room towards the sofa, Othniel made to stand and offer me his place, but I gestured for him to stay seated and took my own spot on the floor at their feet.

“I think this calls for cigarettes,” I said. “Paris?”

He rummaged for his silver case and passed it to Father Eagle, who solicitously removed two of the gilt tubes and place one in my hand. “You’re a good woman, Dr. Vivian,” he said.

I bowed my head. “You’re a good man. And I’m certain Othniel will be a wonderful wife for you.”

Paris aimed a playful kick wide of my hip. The Father of the Riverborn laughed, struck a match, and bent to light our three cigarettes from the same steady flame.

Saturday, September 03, 2011

0 comments:

Post a Comment