We did not learn of it in the usual way.

On September 20, 1765, a black carriage shuddered to a halt outside my family’s house in Langogne. The final rain of summer fell in warm gossamer sheets, washing black Languedoc mud from the coach’s wheels and the shoes of its occupants. My sister Antoinette emerged, dressed outlandishly as usual with travel-stained lace and ropes of damp fox-fur at her cuffs; if it weren’t for the black ribbons and grave expressions her companions wore, I would never have known something was amiss.

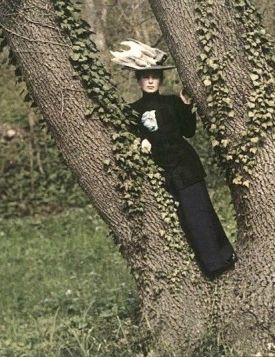

“Mélisande!” Antoinette opened her arms to me as I flew down the brick steps, her white clock flowing off her shoulders like cream. The rain sheeted over her sharp cheekbones and caught, pearl-like, on her eyelashes and crisp red curls.

“Bienvenue, sister,” I said hesitantly, holding her out at arms’ length. All around us, footmen vied with the family servants to get her luggage in out of the damp. None of Antoinette’s men would meet my gaze. “Where’s Michel?”

At the sound of her husband’s name, my sister pursed her lips in a sharp, familiar gesture of despair.

That was how we learned that our protection from la bête du Gévaudan had run out.

“And what, pray tell, is so damn hard about writing a letter?”

“Père.” Antoinette frowned, her long fingers loosening the clasp of her cloak. A slow puddle spread across the parlor floor at our feet. “Do you mean to say you aren’t pleased to see me?”

“Don’t needle him,” I whispered. Antoinette’s only answer was to shove her cloak into my arms and hiss at me to hang it up.

Papa leaned back in his chair. His dark eyebrows—the only spots of color in his face—met in a straight line over his crooked nose. “You should be in Paris, Antoinette.”

“There’s nothing for me there.”

“Célestin Charbonneau is there.”

“As I said.” She folded her hands at her waist, resting her elbows on her hips. “Nothing for me.”

Apparently, that's as far as I got. Your guess is precisely as good as mine.

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

I appreciate the useful information and your hard work. I also came across a similar blog you might like. Thanks again!

ReplyDeletewatch battery replacement